“Ransom is probably the worst part of the game. He’s like a total a**hole, right?”

That’s Ron Gilbert, co-creator of Thimbleweed Park on Ransom, a dirty-joke-telling clown you’ll love to hate. Gilbert’s description of him couldn’t be any more apt: from the moment I take control of Ransom at PAX East, it’s clear the guy is a colossal jerk. In the world of Thimbleweed Park, though, behaving like a generally rotten individual has made Ransom filthy rich. On stage, he’s almost like Daniel Tosh’s TV persona trapped in the body of Bozo the Clown. He spews vulgarities nonstop and aims horribly personal attacks directly at audience members.

He can dish it, but can he take it?

In most games, the characters you love to hate aren’t those you play as; they’re NPCs, which makes it easy to outright loathe them and divest yourself from their interests. But in Thimbleweed Park, you have to play as this miserable SOB, which means his goals are yours. If you want to play the game, you have no choice but to tap into Ransom’s nasty side — which may just be his only side.

“I kind of felt it was important to make him that way, to really make someone who is going to be obnoxious, and you almost don’t like him,” says Gilbert with a seeming misuse of the word “almost” in his description of the character. “You almost don’t want to play as him.”

OK, it’s not actually so awful that you’ll stop playing the game. What’s more, Gilbert and co-creator Gary Winnick have added narration explaining that the audience members who are laughing are only doing so to hide their embarrassment over the painful barbs. Still, Ransom is lousy enough of a person that I look for another way forward other than insulting his audience members for their looks, age, etc.

Alas, there isn’t one, so I settle for dishing out the least-mean-but-still-pretty-terrible insults at my disposal before the remaining dialogue options dwindle and force me to select something truly awful. That’s when Ransom finally gets his comeuppance. The offended party is a mystic who curses the clown to permanently become a walking joke so that he can get the proverbial taste of his own medicine.

Things only get worse for Ransom when his manager quits and reveals that the clown has lost his fortune, his home in Aspen and that his wife has found out about his mistress. Having clearly set up a future quest to break the curse and rebuild Ransom’s shattered life, the demo ends.

Back to the beginning

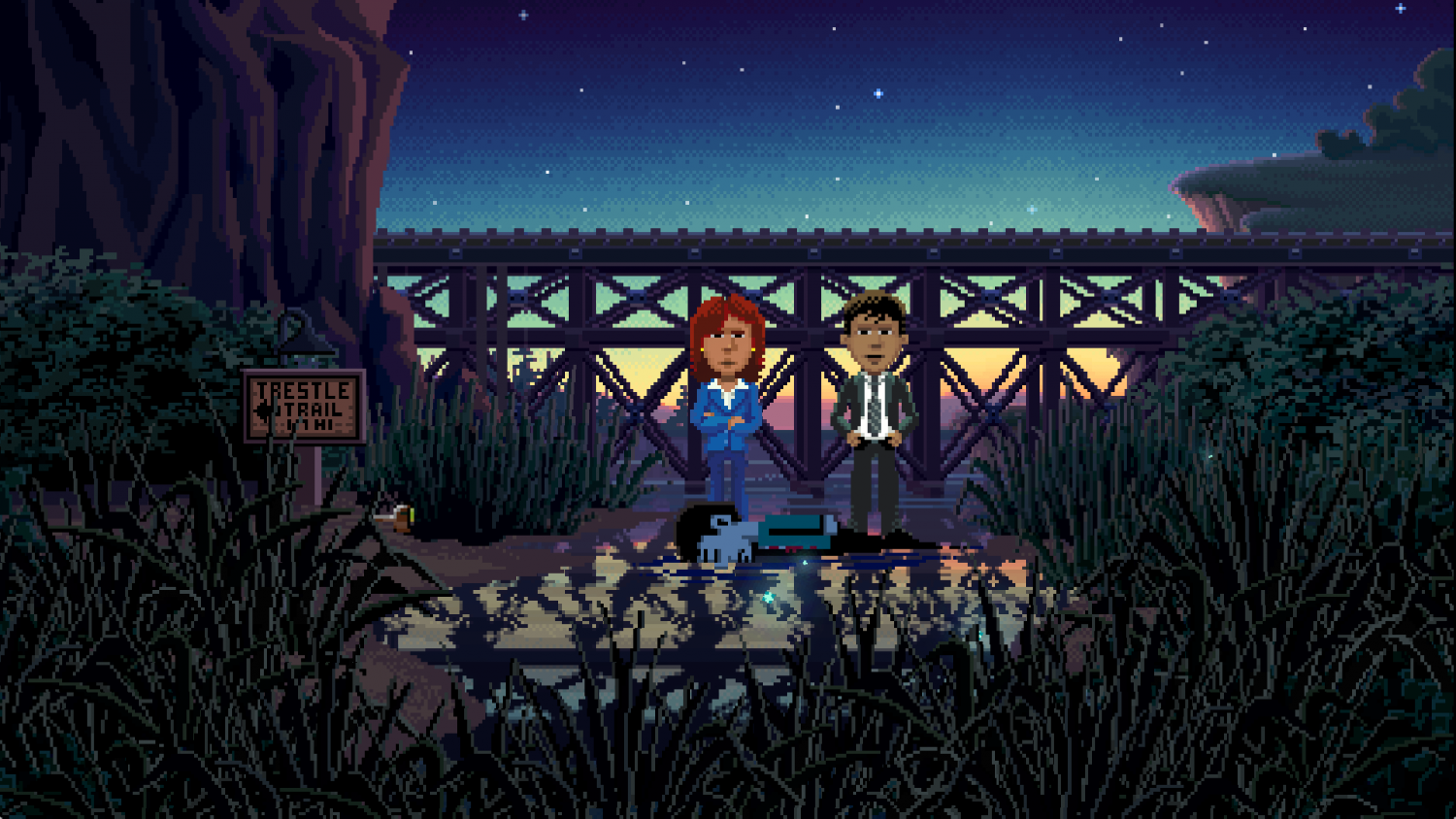

Thimbleweed Park seemingly begins “hours of riveting and hilarious gameplay” earlier, as a loading screen jokingly states. The opening scene, however, immediately betrays the game’s actual beginning. It is so unmistakably vintage in design that I wonder if exiting out would take me to a Windows 95 desktop. Bit-style art depicts a pair of FBI agents who look like doppelgangers of The X-Files‘ Mulder and Scully. The agents are preparing to investigate a dead body, but they’ll only do so if you properly manipulate the inventory and classic point-and-click game actions like “Use” and “Look at,” which appear in large font in the bottom of the screen.

This is an obvious and deliberate return to the genre’s supposed halcyon days of yesteryear, to the type of games Gilbert and Winnick first collaborated on back in 1985 at LucasArts. Though point-and-clicks have been having a sort of don’t-call-it-a-comeback comeback in recent years, they’ve done so with considerably less clicking and considerably greater direct actions. Gilbert and Winnick wanted to change that, albeit while holding onto some modern sensibilities. So how did they decide what to pull forward from the old days?

“We definitely knew the verbs was something we wanted to keep,” says Gilbert. “That’s the core of what this project was about… I knew I wanted to do the dialogues, but that gets into a lot of modern games, so I don’t think that’s such a big deal. Inventory was important. Inventory is also one of those things that’s kind of gone away a lot.”

Along with those verbs and dialogue options, inventory is definitely back in Thimbleweed. As both the FBI agents and Ransom I have to find the right items and select the right action items for manipulating them from the menu in order to solve puzzles. Things are straightforward enough as the agents, but a little bit less obvious later on as Ransom. After uncovering the hidden location of cash needed to pay off a debt, there’s then a bit of a run-around to figure out combination numbers for a safe.

“The thing we wanted to do was get rid of frustrating puzzles and have challenging puzzles,” explains Gilbert. “That’s where a lot of adventure games kind of go off the rails, because they do a lot of frustrating puzzles but not challenging puzzles. That’s something that we knew we wanted to do.”

If what’s shown at PAX is any indication, they’ve accomplished just that. Finding the solution to the safe puzzle doesn’t take too long. More importantly, it’s fun the whole way through and often funny, which is another element Gilbert and Winnick were all too happy to bring back from their earlier games. The team doesn’t possess any secret formula for making all this happen. They just do it somehow, though they don’t always get it exactly right the first time around, says Gilbert.

“There’s no science. That’s just magic, I guess. I don’t know how that works. You just do them, and you do a lot of play testing. We bring a lot of people in to play the game and [we] just watch. We don’t tell them anything, we don’t give them any hints, we just watch them play. And then we watch how it plays out. ‘Oh, they’re getting frustrated at this point because we didn’t give them enough information.’

“Sometimes we can turn a frustrating puzzle into a challenging puzzle just by giving them a little bit of information in the dialogue. And so that’s the kind of stuff we do, and just iterate on that stuff always.”

Stripped down

So if the old style of adventure games were so much better, why did the industry ever get away from them? And who’s to blame for it? Gilbert shrugs at this line of questioning and suggests that “people just like change.” He allows that the genre had been doing the same things for a long time, so developers began trying different approaches in the mid-90s.

“But in my mind it’s sort of stripped away a lot of stuff,” he says. “They kind of stripped away the verbs, and a lot of inventory got stripped away. And I think they stripped away too much stuff, and I think they became too simple.”

Ironically enough, the last game Gilbert directed was The Cave, a more action-oriented adventure game that was sans verbs. He temporarily joined Double Fine Productions specifically to make that game, too. While reviewing The Cave, I found that while it made me laugh thanks to Gilbert’s trademark humor, its puzzles were too often the polar opposite of what he wants them to be: they were more frustrating than fun.

Now he sees the possibility to cycle adventure games back to their roots. And if those supposed “hours of riveting fun and hilarious gameplay” I don’t get to experience at PAX turn out anything like the time I do spend with Ransom and the federal agents, Thimbleweed Park may just pull it off with flying colors.

“There’s a charm to that stuff,” asserts Gilbert, “and it’s important that this stuff should come back, so we’re doing that and seeing if that works or not.”