“This is Adam Orth, creator of Adr1ft,” a PR man states matter-of-factly.

Orth is the game developer best known for causing a 2013 internet riot with his infamous #dealwithit tweet. Here at an AMC Loews theater in Boston the weekend of PAX East, he stands up in front of a handful of media members to talk briefly about his game. The whole scene feels pleasantly at odds with the commotion and excitement (real and feigned) back at the convention center I’ve just left. Orth is soft-spoken and unassuming, and aside from just showing the game, there is scarcely any attempt made to hype up the audience. None is needed, because when I pull on an Oculus Rift moments later, I am immediately impressed by Adr1ft.

The added immersion of the VR headset helps, to be sure. But Orth insists that his game was designed to captivate players with or without another reality strapped to their faces. Certainly some of the enveloping feeling of space’s vastness is lost when the headset comes off. After it does, however, watching XBLA Fans’ John Laster and Jill Randolph play on a regular old TV screen is still a treat. Spectating their non-VR play sessions makes me want to get back into this game that is somehow being built by the small team at Three One Zero.

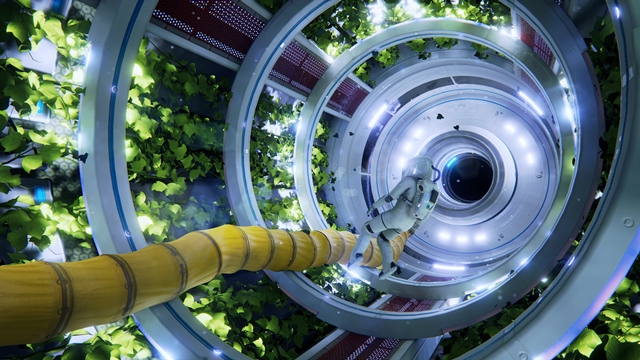

Adr1ft doesn’t seem like something that a diminutive indie developer could create in short order — but that’s exactly what it is. After less than a year in development at Three One Zero, the game’s Gravity-like take on space exploration mission turned disaster is moving. Floating aimlessly through the wreckage of a space station, I take in the little things, like a single leaf escaping from the station’s garden as it collides softly with my helmet. Turning to watch this green speck drift away, I’m dumbstruck and a little frightened by the vast emptiness of space engulfing it. Turning again, I find myself confronted with a familiar, comforting image that I have to assume has left many real-world astronauts breathing a little easier: Earth.

Later, Orth will ask what we think this sort of experience is worth and what games we think it’s in the same class with; he seems sincerely interested in knowing what value others place on his project. It’s a degree of humbleness his many detractors from two years ago might not expect from him.

Straight to the point, then

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey was a “very” inspirational movie for Three One Zero, and anyone who’s seen Gravity will draw some obvious parallels between it and Adr1ft. But though Orth needed to go to a movie theater to show his game off, he didn’t need to go to one to develop a vision for it. For that, all he had to do was piss off millions of gamers and get fired from his job at Microsoft.

He accomplished as much with his aforementioned #dealwithit tweet referencing Microsoft’s since-abandoned plans for an always-online Xbox One. What happened next can only be described as a severe and unrelenting ****storm. Adr1ft‘s player-character doesn’t have a Twitter account (that we know of), but from the outset she nonetheless finds herself surrounded by utter chaos that Orth describes as “a pretty obvious and direct metaphor” for his real-life experiences. Though Adr1ft is yet to be released, its public and press reception has been considerably warmer than Orth’s 2013 suggestion for gamers was, and he says that seeing the responses since Adr1ft‘s public unveiling last December has been “amazing.”

When I ask him if he feels some manner of redemption in that, he pauses to ruminate with a long “uuuuummmm” before deciding that he does not. “I wouldn’t say that it’s a redemption thing,” he says. “I mean, no, not so much. I just want to make something that is cool and moves people, and our team — we’re all in the same boat. We’ve been doing this a long time, and we’re all really excited about this because it’s different and fresh, and it’s really more…” he trails off before finding the right words to continue with. “I’m more interested in exciting people than in making myself feel good.”

Touchy-feely

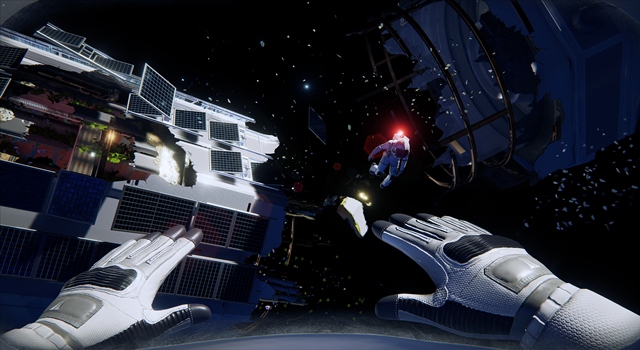

The stakes in the game are considerably higher than a video game console’s proposed DRM policy. The player awakens in a space station that has suffered some sort of catastrophe. The station has been torn asunder, and the astronaut you take control of discovers that her suit is leaking oxygen. As the astronaut, you’ll have to traverse bits of space wreckage while managing your oxygen, which is needed both for survival and for propulsion. The experience differs more than a little bit from the kind of one the members of Three One Zero are used to working on as a unit. In the first half of the last decade, the devs were busying themselves making Medal of Honor games while under the employ of Electronic Arts.

In a past interview with Polygon, Orth said that his team wanted the first game it releases as a studio to be a weaponless first-person experience — but not a boring one. He spoke then of the importance of having fun game mechanics despite the main character not having guns in her hands like players have become accustomed to in first-person games. Orth concedes that accomplishing as much has not been easy.

“It’s so challenging, and it’s so hard to do,” he says. “There’s a lot of games, shooters, that have moments where you don’t have guns for doing stuff, but we have to do that for the entire game. And it’s actually liberating in a way, because it forces us to think of creative ways to do things. And just the little bit that you saw, it’s not a static experience. Your hands are always touching and grabbing things and pulling things and manipulating things.”

The little bit he’s referring to is only the beginning of the game. After watching pre-recorded video of this stretch of gameplay on the silver screen, I take the controls with little in the way of direction. I spend most of my time floating aimlessly about, not really sure what I’m meant to be doing other than reaching out to collect oxygen canisters whenever I find them.

“You’re touching things constantly,” Orth later notes after my play session has concluded, “and I think that really helps immerse players into the game because you kind of really put yourself into that character when you’re physically doing things.”

It feels good to reach out and grab the oxygen containers. It feels good to touch most things while playing, actually. Three One Zero intentionally gave players interesting things to touch and worked to avoid giving them “a Frankenstein pose flying through the world.” Orth says that’s because “little things like holding a box and then floating through a destroyed environment and then letting it go and float out into space and just watching it go forever — it’s immensely satisfying. And it has nothing to do with the game, but it gives the player this sense of agency that they’re affecting the world with their hands, and that’s really important.”

Float on

Though my aimless meandering through space is enjoyable and even borders on breathtaking at times, I wonder if there is more to Adr1ft than this free roaming and oxygen tank collecting. Orth says that there is a linear path to take towards the end game, “but at any time you can go off it and explore and do other things. Now, is that in your best interest? I don’t know. Is there going to be oxygen over there? You don’t know. But it’s very — you know, when we first started doing this our goal was to make this totally open world, and we had to stop almost immediately once we started developing just because we’re not a big enough team to pull that off. And we got rid of the ultimate dream, but I think we found a way where it still has that kind of open exploration vibe.

“And when you’re throwing players into a weightless environment where they can move in any direction, that’s asking a lot. And having a linear path is really important to us, so you can fly through, and you can get awesome narrative bits, but you might not get the whole story. There is stuff off the beaten path.”

We know that making a fun first-person game without any form of combat has been difficult for Three One Zero. The fact that players can wander freely through a large expanse of outer space towards points that may or may not contain something of interest has seemingly compounded that problem. That might lead you to believe the oxygen mechanic was brainstormed as a way to add conflict. In one breath Orth says that’s not the case, but he follows up by admitting that adding oxygen was “the first thing we did because we didn’t have guns.” Those two sentiments appear to be at odds with each other, but they might not be when you consider that oxygen hasn’t always worked the way it does now.

“A couple of months ago we decided to make oxygen a shared resource, so your suit is always leaking oxygen, and since you’re sharing oxygen for life and movement it really kind of creates this awesome game mechanic,” Orth elucidates, “because if you have a tank floating you have to make all kinds of mini decisions in the moment about how to get that. ‘Do I just let the inertia of my movement flip me over there and hope that I get it before my oxygen depletes?'”

At any time you can simply float without using your space suit’s propulsion system, and doing so might give you a better chance of making it to your destination. It might also mean that the time it takes will be too great, though, and you’ll deplete your oxygen reserves through breathing and die from asphyxiation. As such, you have to make on-the-spot judgments of time versus distance when deciding where and how far they want to travel.

There aren’t endless travel options, though. Remember, Three One Zero had to cut out its “ultimate dream” of a full open world because of the small size of its team. Orth insists that despite this, the game’s size has somehow never changed. He says he’s happy with the more linear path the team established for Adr1ft, especially given that it’s made story telling easier. He sounds like a man who isn’t dwelling on the decision.

“So I don’t feel like it was a compromise. I feel like we seriously approached it, and we seriously tried to do it,” he explains. “But in the end our experience told us, ‘If you go down this route, it’s not going to be finished in time, and it’s not going to be as good as it could be.’ Because we simply just don’t have enough people to find all the millions of bugs that just come, and the design decisions around open world really affect how you build the game. So I don’t think it was a compromise. I think we made the absolute best choice. I think doing it open world would have been a mistake.”

How and how much

Predicting a game’s greatness (or not-so greatness) based on a brief hands-on session with the unfinished product is a dicier affair than many gamers might realize. Unfinished software rarely has a lack of moving parts that must be brought together into a cohesive whole, and judging a game by its demo is hardly more fair than judging a book if not by its cover then perhaps by a mere handful of pages read without context. And yet, it’s difficult to resist praising what the small group of developers who have Three One Zero printed on their paychecks have accomplished thus far. I ask Orth how it’s even possible. His answer is simpler than you might expect.

“That’s a great question, and I have a great answer,” he proclaims. “The reason we can make something that’s of this quality is because we’re all veterans, we’ve all been making AAA games for 10+ years.” Orth in particular has just passed his 18th year working in games, and with that figurative adulthood has come the freedom and ability to make what he wants to make. The entire team has dreamed of doing so since their Medal of Honor days, which ended almost 10 years ago — a long time to wait.

“It’s always been our dream,” says Orth. “And when I had the opportunity to call my group of friends up, they all jumped at the chance.”

He thinks that dream is translating well into an actual game. He thinks it’s “awesome,” but don’t take that as overconfidence. After all, Orth isn’t even sure what he should ask for from gamers in return for his dream game. After glancing back at his public relations rep for approval, he reveals that the game will be priced somewhere between $20 and $30, but that he’s not sure how much it’s really worth. He flips the tables and begins interviewing us. What do we think his game is worth? Do we think that, at four hours, it’s too short? What class of games would we put it in?

I tell him that, going off what’s been shown, it’s very impressive that such a small team has mimicked the look and sound of a AAA release.

“That, to me, is incredible,” XBLA Fans Editor in Chief John Laster agrees.

It doesn’t really matter what we think, though. It’s up to gamers to decide whether or not Adr1ft is worth whatever its asking price ends up being. For them, Orth has one last question: “What I always say about Adr1ft is, if there was a director’s cut of Interstellar, and you went to the best IMAX theater, and it cost you $30 to go have an awesome three-hour piece of entertainment, wouldn’t that be worth it?”